Welcome back to our series on the core where it is our intention to increase your understanding of its anatomy, function and role in your rehabilitation. In our previous post, Our Core The Functional Pressure System, we discussed one of the primary functions of the core, which is to create and regulate intra abdominal pressure. The presence and regulation of intra abdominal pressure reinforces our skeletal structure much like that of how carbonation pressure inside a can reinforces the relatively weak aluminum frame.

Because we are humans and not cans, we have to consider that our spine, which is made up of 24 individual bones and designed to move, requires additional support outside of relying on intra abdominal pressure alone. Our spinal column serves to protect our nervous system and is an attachment site for the muscles, ligaments, nerves, guts and fascia, it stores kinetic energy and it helps transfer the loads of the body into our base of support. To function effectively, the spinal column needs to be both stiff and flexible at the same time. This dynamic dance of stiffness and flexibility is orchestrated by the brain’s incredible ability to control a symphony of muscles around the spine.

In this post we would like to:

- Discuss how the local muscles around the spinal column function in creating spinal stabilization

- Define efficient neuromuscular function

- Discuss how injury/postural choices impact muscular function (for additional information regarding posture, check out our blog Get Over Yourself)

- Provide several exercises to help start the process of integrating these muscles back into our function

Let’s take a look at some of the smaller muscles around the spinal column that do not create intra abdominal pressure, but work with the pressure to enhance spinal segmental stabilization.

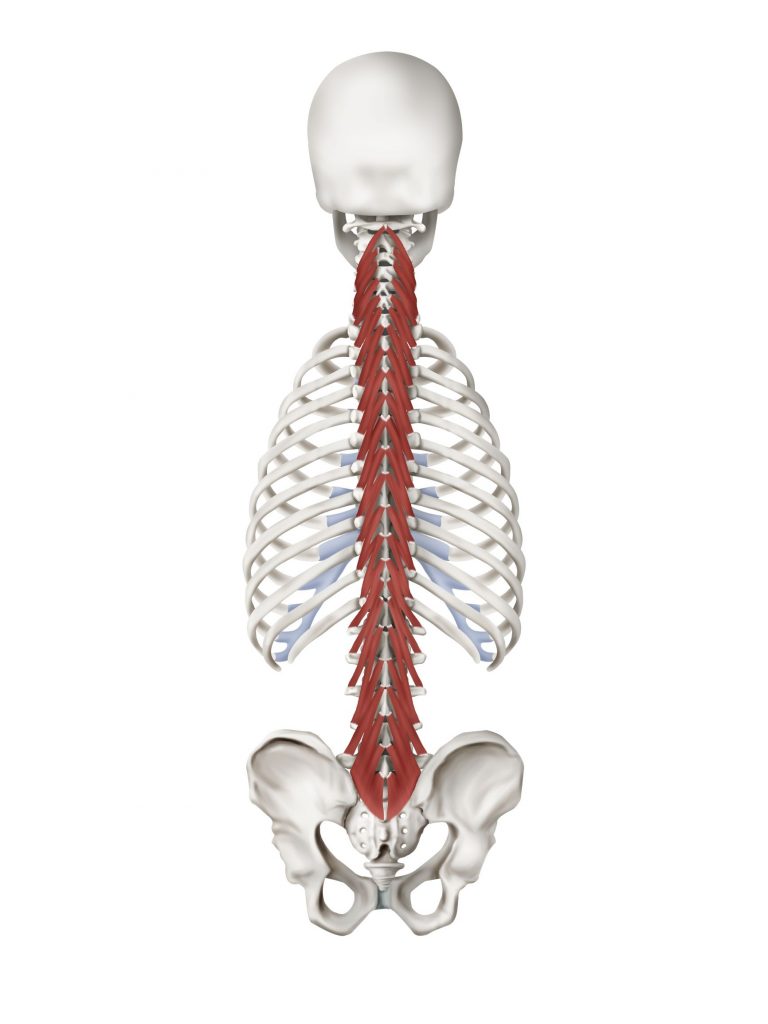

The Multifidus and Transverse Spinalis Muscles

The multifidus and spinal rotator muscles span the whole length of the vertebral column but is most developed in the lumbar area. These muscles form a complex of short, local muscle struts that when working together form the local core stabilizers on back and sides of the spine.

The Psoas

The fibers of the psoas originate from the vertebral bodies and discs of the lower thoracic and lumbar spine and insert on the thigh bone. Contracting the psoas pulls the thigh bone up when the leg is free to move, however if the leg is fixed, contraction causes the spinal column to bend backwards and side bending to the same side.

The psoas muscle often gets a bad rap for being overly tight, spastic and a source for lower back pain. Although psoas dysfunction is common and soft tissue mobilization can serve an important role in restoring normal function, the muscle should be appreciated, not demonized, as it serves an important role in our spinal stabilization system.

The deep fibers of the psoas close to the spinal column have a high concentration of slow twitch muscle fibers and attach to the spinal discs highlighting its role as the primary stabilizing muscle strut on the front of spine. Psoas fibers blend with the root of the diaphragm further assisting the postural role our diaphragm serves.

Interesting fascia fact: the fascial network of the psoas can be traced all the way up to mid-thoracic spine to approximately the T5 level where it blends with fascia from the deep neck flexors. Functionally these muscle groups cannot be separated.

Additionally, the transverse abdominis, deep fibers of the quadratus lumborum, pelvic floor and diaphragm serve to create spinal stability and are highlighted in our last blog. All of these muscles are connected both directly to each other and indirectly through the fascial system.

Together, this myofascial system creates a circumferential corset around the spine creating the active system that provides the dynamic stiffness to effectively reduce/prevent adverse vertebral motions thereby protecting the ligaments, joints and discs from potential injury

These core muscle contractions are created by an automatic/subconscious (meaning you shouldn’t have to think about it) activation of the slow twitch muscle fibers. The term we use to describe this in the clinic is your Automatic Core EngagementTM or ACE, and we use a variety of tests in the clinic to help determine if your ACE is efficient in any functional position.

Implications of Core Dysfunction

Core muscle weakness is associated with chronic lower back pain 1,2. The multifidus has been shown to become inhibited (turned off) after spinal injury and does not turn back on, even after the symptoms of the injury have subsided 3, leading to increased risk of injury in the future. Additionally, cross-sectional studies of the muscles in patients with chronic lower back pain have fatty infiltration into their multifidus muscle group (shown in white in the picture below). Furthermore, studies looking at functional MRI’s show the brain actually loses an accurate representation of the transverse abdominis and multifidus in individuals with chronic lower back pain5.

On a cellular level, Slow twitch fibers have energy systems that support prolonged muscle contractions and therefore do not fatigue quickly. Fast twitch fibers contract to create movement or perform short, repeated movements, but fatigue quickly when asked to perform a sustained contraction. Other terms that could be used to differentiate the fast and slow twitch commonly used in Functional Manual Therapy TM are tonic and phasic fibers. Keep this?

Facilitate Your Core – the First Step

The Functional Manual TherapyTM curriculum defines efficient neuromuscular function as:

“The neurophysiological ability of synergistic muscles to initiate a contraction with proper strength and endurance for the given task, including the ability to return to a state of muscular relaxation.”

The key term we are going to focus on in the above definition is initiation. As mentioned above, muscle can become inhibited and later replaced with fatty infiltrates in a state of pain or after injury. Before muscles can be strengthened, the basic function of muscle activation and coordination need to be reinstated and initiation is the first step.

To facilitate a muscle, there are several options. In the FMT approach frequently we utilize prolonged end range holds to disinhibit/facilitate/tun back on muscle groups commonly found around the spinal column.

A prolonged hold is tough and takes effort to “break through” to the shut down muscles. When recruited maximally, there is a spreading of muscle energy into and throughout the deeper layers and more densely inhibited muscle fibers. Isometric holds increase the volume of muscle recruitment, forcing deeper and inhibited muscle groups to fire more comprehensively. In doing this repeatedly, the body will adapt a more efficient response from the fast and slow twitch fibers. After muscle groups are effectively turned on and working together, movement patterns can functionally trained in a progressive format to build strength and endurance.

When performing the following exercises consider the following guidelines:

- Achieve the positions shown on the video, make them comfortable with supports as necessary

- When initiating the contraction, come on slowly and build into a more maximal effort

- You must continue to breathe throughout the exercise normally

- Do not hold your breath.

- Keep your whole tongue on the roof of your mouth

- Maintain the efforts to and through fatigue:

- this is often accompanied by a sensation of shaking in the muscle groups

- If you can work through the shakes and achieve better stillness and improved ability to breath normally, you are achieving the goal

- They should not cause your pain to increase or spread

- You should be screened by your FMT specialist for your safety prior to performing these exercises

Resisted diaphragm

Abdominal series

Prone ballerina

Basking seal

Triple extension

- Zheng Y, Ke S, Lin C, Li X, Liu C, Wu Y, Xin W, Ma C, Wu S. Effect of Core Stability Training Monitored by Rehabilitative Ultrasound Image and Surface Electromyogram in Local Core Muscles of Healthy People. Pain Research and Management. 2019;2019.

- Kliziene I, Sipaviciene S, Klizas S, Imbrasiene D. Effects of core stability exercises on multifidus muscles in healthy women and women with chronic low-back pain. Journal of back and musculoskeletal rehabilitation. 2015 Jan 1;28(4):841-7.

- Hides, Julie A. PhD; Richardson, Carolyn A. PhD; Jull, Gwendolen A. MPhty Multifidus Muscle Recovery Is Not Automatic After Resolution of Acute, First-Episode Low Back Pain, Spine: December 1, 1996 – Volume 21 – Issue 23 – p 2763-2769.

- J. Antony, K. McGuinness, N. Welch, J. Coyle, A. Franklyn-Miller, N.E. O’Connor, K. Moran. An interactive segmentation tool for quantifying fat in lumbar muscles using axial lumbar-spine MRI. IRBM: 2016 Volume 37, Issue 1, Pages 11-22.

- Xin Li, Howe Liu, Le Ge, Yifeng Yan, Wai Leung Ambrose Lo, Le Li, Chuhuai Wang, “Cortical Representations of Transversus Abdominis and Multifidus Muscles Were Discrete in Patients with Chronic Low Back Pain: Evidence Elicited by TMS”, Neural Plasticity, vol. 2021.

- Paoletti, Serge. Eastland Press Inc. 2006