There are many things that can cause dizziness:

- Medication

- Dehydration

- Anxiety

- Stroke

- Aneurysm

- Vestibular disorders

- Concussion

The most common patient story I hear is an experience with sudden onset of dizziness resulting in a trip to the emergency department (ED). All of the appropriate testing is completed ruling out stroke, aneurysm and dehydration, however imbalance and dizziness continue and they are diagnosed with vertigo. The term vertigo is often used as a catch-all term for anyone feeling dizziness without a specific origin. Commonly the vertigo diagnosis from the ED is further investigated and a term, vestibular disorder, or dysfunction may come about with a visit to a Neurologist or Otolaryngologist. This is when a referral to a Physical Therapist who treats patients with vestibular dysfunction is key. Why? Because the sooner you can get in to see a Physical Therapist who treats vestibular disorders the better. This is not always the order that things happen, but you can advocate for yourself by asking your physician for a referral. For the purposes of this blog I am going to focus on the function and anatomy of the peripheral vestibular system. For more information about vestibular PT please read the blog coming soon on Vestibular Rehabilitation Therapy (VRT).

If your dizziness is due to your peripheral vestibular system, here are some of the things you may feel:

- Dizziness

- Imbalance, unsteadiness, or loss of equilibrium

- Vertigo; spinning component to your perception of movement

- Brain fog and cognitive changes; a lot of energy is spent maintaining equilibrium so other activities are not as efficient and feel slow

- Tinnitus; this is an abnormal noise in one or both ears

- Hearing loss

- Visual impairment

- Nausea

- Psychological changes due to nature of symptoms; anxiety and or depression may present

- Motion sickness; this occurs when the central nervous system receives conflicting information from the vestibular and visual systems

So what exactly is the Peripheral Vestibular System?

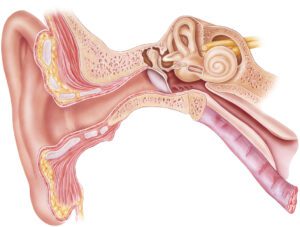

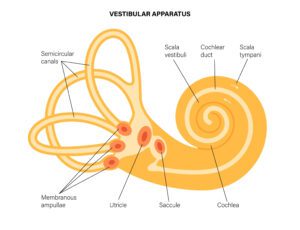

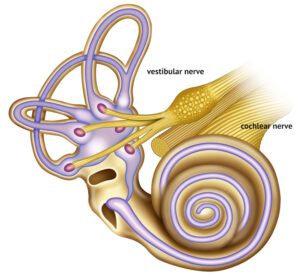

The peripheral vestibular system is about the size of a dime and is embedded in your temporal bone on either side of your head. It is made up of the inner ear structures and the nerve pathway to the brain. The inner ear is made up of the cochlea, endolymphatic sac, and vestibular apparatus: utricle, saccule, and semicircular canals. The cochlear and vestibular nerves run from the inner ear to the brain. Running alongside these nerves is the facial nerve, however it is not directly involved in the vestibular communication with the brain.

The semicircular canals detect angular motion (rotation and side bending of your head) and the utricle and saccule detect linear acceleration and deceleration (walking or sitting). The utricle detects horizontal linear acceleration (car moving) whereas the saccule detects vertical linear acceleration (elevator). Note that these structures detect acceleration. That is why once you are on the freeway going a steady 65 mph you no longer detect you are moving at such high velocity, but you felt it 0 to 65 on the on ramp.

Both structures have a gelatinous layer which covers receptor cells called hair cells. On top of this there are calcium carbonate crystals called otoconia. These crystals, also known as ear rocks, are what allows the gelatinous layer to be sensitive to gravity. With movement, gravity and inertia works on the crystals which moves the gelatinous layer therefore bending the hair cells. When the hair cells bend there is a change that happens in the cell which accumulates into an impulse sending information to the brain.

The semicircular canals are oriented in 3 different planes (anterior, horizontal and posterior) at 90 degree angles from one another in order to detect angular motion or rotation or sidebending of the head. They do not have otoconia but do have ampulla at the base of each canal. The canals and the ampulla are filled with what is called endolymph. This is like a saline solution but it is high in potassium instead of sodium.

Within the ampulla there is a specialized structure called a cupula. Within the cupula there are multiple hair cell receptors positioned around one long receptor called kinocilium. When the cupula gets pushed or pulled during movement from the flow of the endolymph it bends the hair cells either towards or away from the kinocilium and converts the movement into electrical impulses to the brain.

The signals coming from the vestibular apparatus travel along the vestibular nerve. The nerve has a superior and inferior part. Damage to the vestibular nerve commonly affects the superior aspect because it travels through a more narrow canal. This damage affects the utricle, part of the saccule, anterior and horizontal canals. Some conditions such as neuritis affect both superior and inferior parts of the vestibular nerve while other conditions such as labyrinthitis affect both the vestibular and cochlear nerves causing hearing loss in addition to vertigo and imbalance.

If one side of the vestibular system is disrupted, this will immediately cause vertigo, dizziness, imbalance and often nausea and vomiting. This occurs because dual signals, one from each side of the head, gives the brain a sense of spatial awareness as well as information to stabilize the eyes. Symptoms with disruption of signal, which can last for several hours to several days, until the brain learns how to reinterpret the signals. When the body and brain do not reset on their own, this is when Vestibular Rehabilitation Therapy (VRT) is needed.

It is important to note that VRT in isolation will treat the vestibular system and its interaction with the brain. Using VRT in conjunction with the three pillars of Functional Manual Therapy; mechanical capacity, neuromuscular function and motor control allow the therapists here at IPA Physio to treat you as a whole. If you feel you would benefit from evaluation and treatment or if you want to learn more please contact us, we’re here to help.

Resources:

Somisetty S, M Das J. Neuroanatomy, Vestibulo-ocular Reflex. [Updated 2021 Jul 31]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK545297/

Fox, DPT, K., 2014. The Peripheral Vestibular System. [free article] Available at: <https://vestibular.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Peripheral-Vestibular-System_48.pdf> [Accessed 14 February 2022].