A muscle strain occurs when the muscle / tendon unit is overstretched or cannot tolerate the force output, and the muscle fibers get over-stretched or torn. Muscle strains are graded on a three point scale:

- Grade 1 (mild) – minor stretching or tearing of muscle fibers. Typically pain is mild and there is no swelling or bruising present.

- Grade 2 (moderate) – moderate damage to muscle fibers. Pain is moderate and swelling and bruising may be present. Strength and mobility are impacted.

- Grade 3 (severe) – a complete tear of the muscle. Pain is severe and there is swelling, bruising, and complete loss of muscle function. May require surgery.

Causes of Muscle Strains

Muscle strains can occur suddenly or progress slowly over time. When a muscle strain occurs suddenly the athlete will experience sharp pain and immediate impaired function. A gradual onset is often first perceived as asymmetric soreness, tightness, stiffness, or tension, but progresses in severity if the aggravating movement / activity continues. Certain muscles are more prone to a sudden onset vs gradual onset. For example a strain of the medial hamstring muscles (inner thigh) may occur due to gradual excessive load, whereas a strain of the lateral hamstring muscles (outer thigh) typically occurs due to a sudden acceleration / deceleration moment while sprinting. A calf strain involving the soleus muscle typically occurs due to gradual excessive load, such as endurance running, whereas a calf strain of the gastrocnemius typically occurs due to a sudden acceleration / deceleration or jumping movement.

Common causes of muscle strains include deconditioning / weakness, poor flexibility, sudden explosive movements, and inconsistent loads – i.e. a sudden increase in sprinting, throwing, kicking, jumping. As with most injuries, previous history of muscle strain is a significant risk factor for future injury.

Fascial dysfunction and poor nerve mobility may be a risk factor for muscle strains. In the lower leg, for instance, fascial tightness is associated with a continuum of soft tissue injuries ranging from muscle strains, tendonitis, shin splints, compartment syndrome, and potentially stress reactions in the tibia and/or fibula.

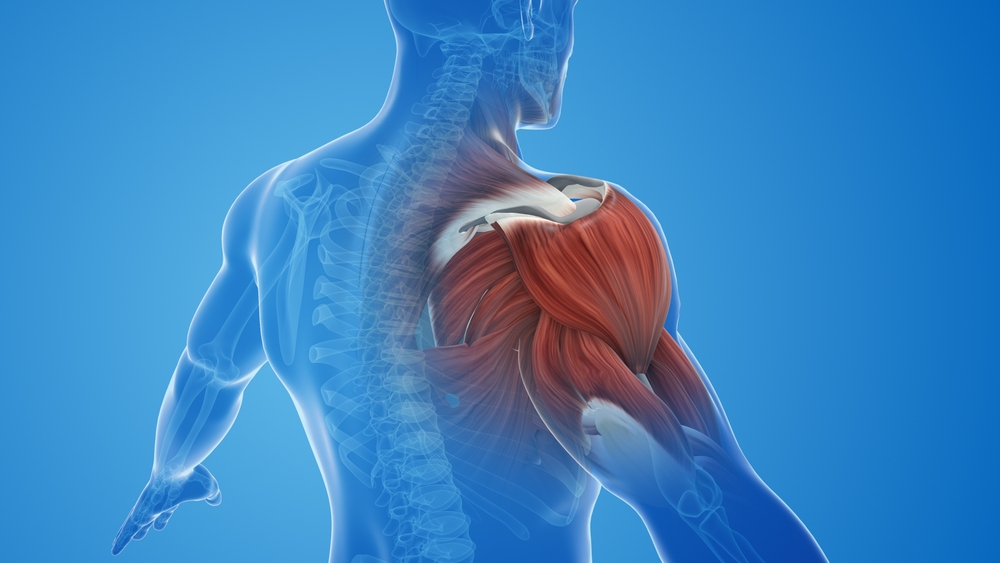

Muscle strains typically occur in the lower extremities (hamstring, groin, calf, quad), abdomen, and shoulder, and can happen to any muscle.

Treatment of Muscle Strains

If a muscle strain is suspected, a thorough physical examination should be performed by a sports medicine doctor, physical therapist, athletic trainer, chiropractor, or other qualified professional. Typically the physical exam is sufficient for diagnosis, but if further clarity is needed, a diagnostic ultrasound or MRI can confirm the diagnosis and assist in grading the injury allowing for a more specific and efficient return to play. .

Follow this GAME PLAN for a Grade 1 strain. Typically an athlete can return to sports participation in 2-3 weeks following a Grade 1 strain, although individual timelines will vary.

RELATIVE REST PHASE – Days 1-2 (initial 24-48 hours)

During this time frame it is important to modify or avoid any activities that cause pain or strain to the injured tissue. Repeat with me, ‘don’t pick the scab!’ If a particular movement or activity causes pain, you must stop or modify that activity.

Walking is generally beneficial and you can walk to tolerance. Avoid stretching or strengthening that directly impacts the strained muscle.

Modalities and other supports may be helpful

- Ice is an analgesic and can have an anti-inflammatory effect. Icing for 10-15 minutes up to every 2 hours immediately following injury + post-injury Days 1-2 can help with pain management and minimizing swelling.

- Photobiomodulation / Laser – this has been shown to accelerate the healing cascade in the body through enhanced ATP (the primary source of cellular fuel) production. The benefits are extensive and include reduced oxidative stress, improved collagen synthesis, improved vascularization and acceleration of the inflammation process.

- Compression may help limit or reduce pain and mild swelling.

- Electrical muscle stimulation (EMS) – this can help to relax muscles and relieve discomfort, as well as decrease mild swelling and pain.

- Anti-inflammatory creams (such as Voltaren), homeopathic creams (such as Arnica) or CBD creams can be used, and may help reduce inflammation. Pain relieving creams such as Tiger balm, Biofreeze, and Icy Hot can also be used to manage pain, but will not expedite the healing process.

- Functional Manual Therapy (FMT) – FMT is the most effective form of physical therapy. FMT utilizes soft tissue / massage and joint mobilization techniques to re-establish optimal mobility of the injured muscle and the surrounding tissues, as well as enhancing joint mobility of the surrounding joints to enhance muscle function. Once the mobility is restored the emphasis shifts to optimizing neuromuscular control and muscle function. Once all of the right muscles are firing at the right time the emphasis shifts to integrating this injured region into the whole body through body mechanics training, gait training, and sport specific training. Click here to find an FMT near you.

RECOVERY AND RESOLUTION PHASE – Typically around Day 3 you can initiate gentle stretching and strengthening. Pain up to 3-4/10 is okay if it does not get worse while exercising. Research studies and our experience have shown that this amount of pain does not interfere with healing and leads to better outcomes related to return to play.

Early cardio: Continue walking and try to walk at least 10,000 steps / day. Initiating cycling or other alternate form of cardiovascular exercise will typically be helpful, as this reinforces blood flow, mobility, and cardiovascular endurance during this early phase prior to returning to jogging / running.

Strengthening: Direct strengthening – start with submaximal isometrics of the injured muscle group (sustained contractions typically held initially for 5-10 seconds and progressed in intensity and duration) and progress to controlled concentric and eccentric contractions. A google search of ‘isometric’ OR ‘concentric’ OR’ eccentric exercises for INSERT INJURED MUSCLE’ will yield some good options. See below for a sample exercise progression for a quad strain:

Isometric Quads (Quad Set) → 2-3 sets of 15-20 reps (10 second hold)

- Start at 50% force and build up

Progress to → Isometric wall sits in a range that is pain not exceeding 4/10

- 1 set of 10 reps 15-20 second holds. Work up to 3 sets of 30-60 second holds

Progress to → Double leg slant board squats (then progress to single-leg)

- 3 sets of 6-8 reps

- 3-4 seconds down (eccentric phase)

- 2-3 seconds up (concentric phase)

Assisted reverse nordics using pull-up assist band OR no assistance

- 3 sets of 6-8 reps

- 3-4 seconds back (eccentric phase)

- 2-3 seconds return to neutral (concentric phase)

Indirect Strengthening: Be sure to strengthen all related muscle groups and the entire body. During this phase you should also be progressing loads during multi-directional strengthening. Blood flow restriction (BFR) training can be helpful during this recovery phase. For more information on BFR see this blog.

- Stretching: Keep all stretching active. DO NOT perform prolonged static stretching of a strained muscle, as this may aggravate the problem and prolong healing. Move slowly and controlled into and out of the stretch, and only stay in the stretched position for 5-10 seconds at a time prior to moving out of the stretch.

- Return to jogging: When you can walk pain-free, you can begin jogging. Start with a walk / jog protocol such as walking 1 minute : jogging 30 seconds x 8. If you tolerate this well, progress slowly as you increase your volume and speed. *If you are a swimmer or water-based athlete, you can follow these guidelines related to returning to water-based activities as well.

- Return to sport specific activities: Sport specific activities can be initiated when you are able to jog pain-free and range of motion and strength are symmetric (equal to opposite side) and back to pre-injury baselines. Gradually progress sport-specific skills, high speed running, and jumping / plyometric activities.

- Return to play: In order to return to competition, an athlete should be gradually reintegrated into full training for approximately 1 week for every 2 weeks that they were out prior to competing in a game / match. This means that if they take 2 weeks with a Grade 1 strain to go through the relative rest and recovery and resolution phases, that they should train in full for 1 week prior to being available for game / match minutes. It is also prudent to limit game / match minutes upon return. For example, a basketball player returning from a calf strain may only be recommended to play one quarter in their first game back, and gradually progress to full availability over the course of 4-6 games. This will decrease the likelihood of reinjury. A soccer player may be recommended 15-20 minutes in their first match back. It is nearly impossible to completely simulate game speed and intensity in training.

A Grade 2 strain will typically take 4-6 weeks to return to sports participation. Typically each phase outlined above will take twice as long. For Grade 2 strains or recurrent strains platelet poor plasma should be considered to enhance healing and return to play. Platelet poor plasma is different from the more well-known platelet rich plasma in that it may stimulate anti-inflammatory effects and expedite return to play.

Restoration and Resilience Phase

Restoration: It can take up to 8 weeks for the injured muscle tissue to fully heal from a Grade 1 strain and up to 4 months for the muscle tissue to fully heal from a Grade 2 strain. These tissues, and all of our body’s tissues, are constantly remodeling (for years). As you can see from the above timelines, people are able to return to play much earlier than the time point that the tissues are fully remodeled. But, the ongoing remodeling highlights the importance of continuing rehabilitation exercise programs, and ongoing monitoring past the return play period.

Resilience and Prevention: Progressive and consistent loading is key to preventing muscle strains, and very likely the MOST important variable at play. This means that strength programs and running programs (total running volume and high speed running volume) should be progressive and consistent. Athletes are more likely to suffer a hamstring strain if their high speed running volume is inconsistent or excessive. Soccer players are more likely to suffer a groin or hip flexor strain if their kicking loads are inconsistent or excessive. Pitchers are more likely to injure their elbow or shoulder if their throwing loads are inconsistent or excessive. To prevent recurrent muscle strains and become as resilient as possible, incorporate the following:

- Continue a well-rounded mobility and strength program.

- As discussed above, for at least 4-8 weeks following return to play you must remain very diligent in continuing the rehabilitative exercises and loading progressions that you established during recovery.

- Decrease system inflammation

- Inflammation due to stress, lack of sleep, poor nutrition, environmental allergies, and other factors will limit healing and make you more susceptible to injury

- Optimize nutrition and hydration

- Injured tissues will benefit from increased protein and water intake

- Optimize rest and recovery continuously

- Sleep is the most important recovery tool. Aim for 8 hours per night at minimum, particularly when injured.

- Other recovery tools include hyperbaric oxygen therapy, cold plunge, infrared sauna, laser

- Optimize technique

- Working with a physio, strength coach, technique coach who knows your specific sport demands may help to reduce the risk of injury / re-injury

- Always perform a good warmup

- A good warm-up gets you moving in all directions at various speeds and anticipates the demands required of the sport / activity that will follow. This should take approximately 15-30 minutes

It is our hope that this information empowers you to bounce back and return to play as soon as possible and better than you were before this setback. Think of it like a slingshot – you get pulled back and then shoot forward! For more information, a more personalized program, and expert hands on care, please contact your local IPA Physio office to schedule a consultation.